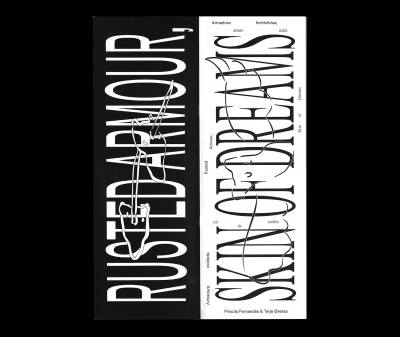

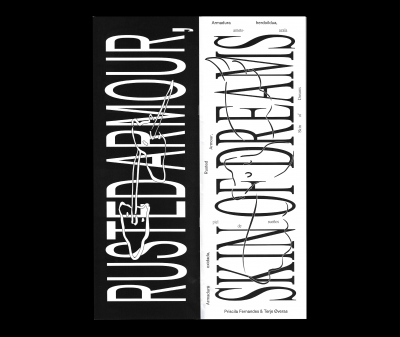

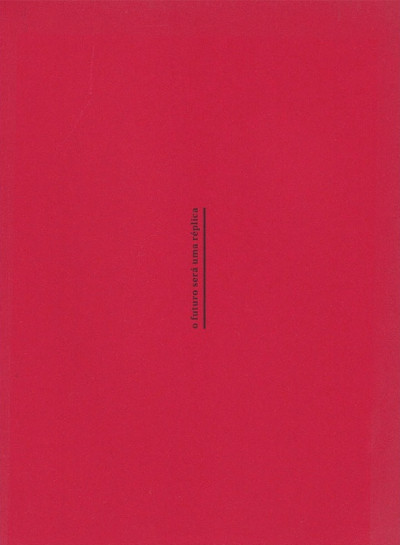

Priscila Fernandes

This text integrated the exhibition Working as if, at Roca Umbert.

Published in 2019

For some time now that I’ve been looking at the possibilities of buying an iRobot Romba vacuum cleaner. To me, the prospect of doing nothing while my smart cleaner robot cleans the house is highly compelling. And it will be fun to come home and see what this little robot has been up to, it could become a pet replacement – Have you been a good robot? Who’s a good robot, who is?

Like in Blade Runner’s replicant Pris, a basic pleasure model for the military clubs of outer colonies (footref: 1), so is my dream iRobot being developed by the manufacturer that provides robotic technology for the United States army and police force (footref: 2) .

Science fiction movies show us a future that is a replica of the present: we now have robots for direct combat and minesweeping, robots in factories and health industries, benign robots for care and leisure, for pleasure and the sex industry. The cyberpunk aesthetics in films like Blade Runner, Wall-E, Strange Days and Valerian and the city of a Thousand Planets bring landscapes that are dense with skyscrapers displaying the brands that own us. These films explore our anxieties with dangerous forms of corporate domination, surveillance, robot wars, the collapse of the environment and climate change. (footref: 3)

If in the film Metropolis leisure is an activity for the high class, the highest achievement is to cultivate oneself and not to work; in cyberpunk films, leisure is the dirty activity of the criminals and degenerates. It’s in the filthy dark streets we encounter the clubs, bars and casinos frequented by the swindlers, the outlaws, smugglers and gangsters, cyborgs, droids and numerous alien races. In that sense, Star Wars‘ Mos Eisley Cantina is one of the most inclusive spaces in the galaxy, with its exotic clientele moving rhythmically to the jazzy music of the Figrin D’an and the Modal Nodes.

What can these films reveal regarding our associations with time free from work, leisure, and who participates in it?

While the passengers of the starliner Axium enjoy their automated and relaxed lifestyles, WALL-E robots are left behind on Earth to clean all the garbage from decades of mass consumerism. In Downsizing future technology is used to solve overpopulation and global warming by “downsizing” people to live in an eco-friendly and experimental community at Leisureworld. Not only is the dream of a consumerist world achieved (if you downsize the cost of living, money gains more value), it also creates a smaller footprint on the environment. These are acts of resistance through leisure that are, at the same time, capitalism redemptive answer to perpetuate production.

We have imagined pills that can make us always happy (Soma, at Brave New World); virtual vacations to Mars (the dream of factory worker Douglas Quaid in Total Recall); or even in bed, an operating system becoming more satisfying than a person (Spike Jonze’s film HER). Such predictions are no longer futuristic. According to Jonathan Crary, capitalism is the end of sleep, colonising every minute of our lives for production and consumption. (footref: 4) Sleep itself has become part of labour processes, integrated into the professional, public and work functions of our society. (footref: 5)

Where do we go from here when we already have ‘sleeping pods’ in offices and ‘holodecks’ filled with recreational experiences? Where are our 24th century idlers (footref: 6) , the benign activists of the universe exploring new worlds of labour production, seeking out healthy and Pacific forms of living, to boldly go where no man has gone before? Leisure – the final frontier.

(footnote: 1 text: “Bryant: they were designed to copy human beings in every way except their emotions. The designers reckoned that after a few years they might develop their own emotional response. Y’know, hate, love, fear, envy." [Blade Runner])

(footnote: 2 text: Blade Runner, edited by Amy Coplan, David Davies, Philosophy in Films, Routledge New York, 2015)

(footnote: 3 text: Read more at http://www.theguardian.com/games/2018/oct/16/neon-corporate-dystopias-why-does-cyberpunk-refuse-move-on text)

(footnote:4 text: Jonathan Crary, 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep, New York: Verso, 2013)

(footnote:5 text: For further reading: The 24/7 Bed, published in WORK, BODY, LEISURE, for the Dutch Pavilion Venice Biennale 2018.)

(footnote:6 text: From 24th century dartboard to golf clubs, 3D chess and ion surfing, plus a number of alien games such as Volcan’s Kal-toh, Ferengi’s Dabo or the Holodeck, all part of an extensive imaginary around games and recreational activities on board of Star Trek. Read more at http://memory-alpha.wikia.com/wiki/Recreational_activities text )

READ MORE...

Priscila Fernandes

Spanish version of the text that integrated the exhibition Working as if, at Roca Umbert.

Published in 2019

D’un temps ençà estic analitzant les possibilitats de comprar una aspiradora iRobot Roomba. Per a mi, la perspectiva de no fer res mentre el meu robot-mascota de neteja intel.ligent neteja la casa és altament convincent. Has estat un bon robot? Qui és un bon robot, qui és?

Les pel.lícules de ciència ficció ens mostren un futur que ja és una rèplica del present: ara tenim robots de combat i detectors de mines, robots en fàbriques i indústries de la salut, robots benignes per a la cura i l’oci, per al plaer i la indústria del sexe. L’estètica cyberpunk en pel.lícules com Blade Runner, Wall-E (2008), Strange Days (1995) o Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets (2017) exploren les nostres ansietats amb formes perilloses de dominació corporativa, vigilància, guerres de robots i el col-lapse del medi ambient i el canvi climàtic.

Si en la pel.lícula Metropolis (1927) l’oci és una activitat per a la classe alta, el major assoliment és no fer res, no treballar, en les pel.lícules cyberpunk, l’oci és l’activitat bruta dels criminals i els degenerats. Els clubs, bars i casinos són freqüentats per estafadors i contrabandistes, droides i alienígenes. Un bar de la ciutat Mos Eisley de Star Wars (Episodi IV, 1977) és un dels espais més inclusius de la galàxia, amb la seva clientela exòtica que es mou rítmicament a la música jazzística de Figrin D’an i els nodes modals. Què poden revelar aquestes pel.lícules sobre la nostra relació amb el temps lliure, el treball i l’oci?

Mentre els passatgers del Starliner Axium gaudeixen dels seus estils de vida relaxats i automatitzats, els robots es queden a la Terra per netejar totes les brossa de dècades de consumisme massiu. A Downsizing (2017) la tecnologia s’utilitza per a resoldre el problema de la superpoblació i l’escalfament global “reduint” a les persones perquè visquin en una comunitat ecològica i experimental a Leisureworld. No només s’aconsegueix el somni d’un món consumista (si redueixes el cost de la vida, els diners arriben per a tot i més), també es redueix la empremta ecològica. Aquests són actes de resistència a través de l’oci que són, al mateix temps, una resposta redemptora del capitalisme per perpetuar la producció.

Hem imaginat píndoles que ens poden fer sempre feliços (Soma, a Brave New World, 1980); vacances virtuals a Mart (el somni de l’obrer Douglas Quaid a Total Recall, 1990); o un sistema operatiu més satisfactori que una persona (Her, 2014). Tals prediccions ja no són futuristes. Segons Jonathan Crary, el capitalisme és la fi del somni que colonitza cada minut de les nostres vides per a la producció i el consum. El somni mateix s’ha convertit en part dels processos laborals, integrat en les funcions professionals i públiques de la nostra societat.

Cap a on anem quan ja tenim llits per dormir a les oficines i sales d’hologrames plenes d’experiències recreatives? On són els nostres ociosos del Segle XXIV, els activistes benignes de l’univers que exploren nous móns de producció laboral, que busquen formes de vida sanes i pacífiques, per anar audaçment a on cap home ha anat abans? Oci: l’última frontera.

READ MORE...