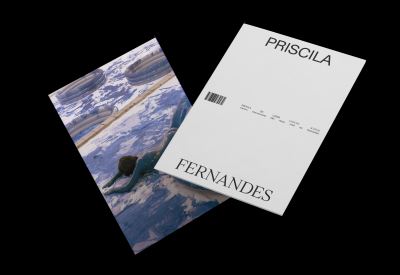

Lars Bang Larsen

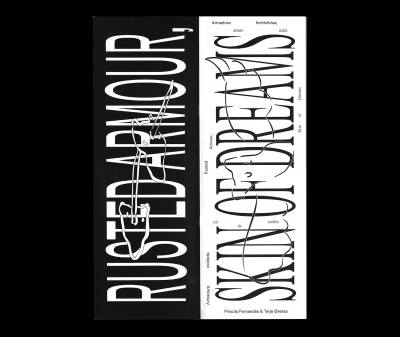

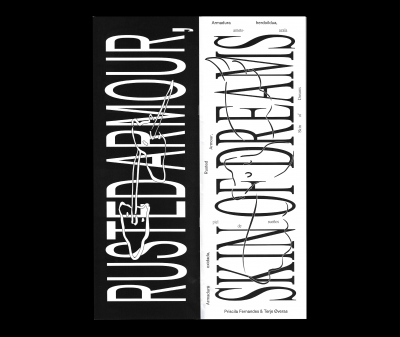

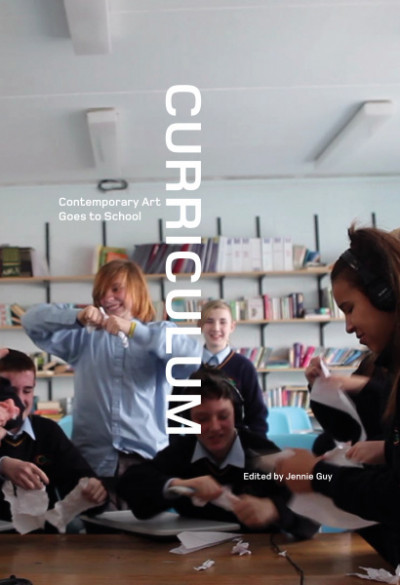

Catalogue text for solo exhibition by Priscila Fernandes, Leisure School, at CIAJG, Guimarães, PT. Curated by Marta Mestre.

Published in 2024

By CIAJG

We Sure Got An Eyeful…!

Labour, leisure and play in Priscila Fernandes‘s history of modern abstraction

We sure got an eyeful of that carnival! And a headful too! Bim bam! And bam again! We whirl around! And we’re carried away! And we scream and we yell! There we are, in a crowd with lights and noise and all the rest of it! Step up, step up! Show your skill, show your daring, and laugh laugh laugh! Whee! Everyone tries to appear to their best advantage, sharp and just a little aloof, to show that usually we go elsewhere for our entertainment, to more “expensive” places as they say.

Louis-Ferdinand Céline: Journey to the End of the Night (1932)

It is an absurd, compelling statement about modern art that is told with the simplicity of an explanation you give to a child, at the same time as it has the elusive air of a wayward philosophical hypothesis. It is this: the artistic ambition of modern abstraction was to make art that never touched the ground. How about that!

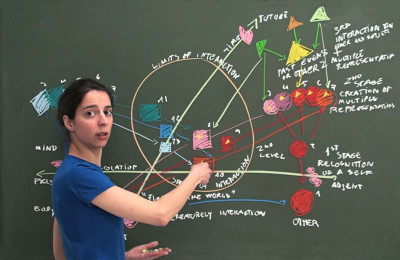

To address modernism s something hovering is how Priscila Fernandes, in her own words, investigates a “correlation between the developments of leisure activities in the 20th century with the different movements of Abstract Art” – a correlation brought about by how the introduction of leisure cultures “into our working lives created a new perceptional and sensorial experience.” Now what does this idea, or postulate imply?

First of all, Fernandes clearly gives modern art a rough ride. In a counter-expression to the fine art tradition that she takes as her subject matter, Fernandes’ video Never Touch the Ground (2020) mimicks the form of a TV show. Donning costumes and props that colourfully quote masterpieces of twentieth century art, the artist here pursues – or performs – the link between leisure culture and abstraction by counter-intuitively accompanying the viewer through play sculptures, theme park attractions, and a skydive centre. Fernandes puts herself on the line, in an immersive meditation on the role of the artist: her exalted mediator is a kind of twenty-first century, bubble gum caricature of the clichéd passionate artist that realizes her unbounded imagination. Wonderfully, there are also sequences in the film acted out by puppet mice, manically engaged in artistic activities. Why mice? We are close to an unhinged sense of the ludic here, in the absence of human actors.

In many of its historical manifestations, abstract art was a blueprint for a better world: one that would be like a latter-day Cockaigne, maybe, with its easy living and absence of toil; or like Charles Fourier’s nineteenth century vision of the ‘phalanstery’, a micro-society where the passions rule with mathematical precision; or maybe like a theme park geared to human needs. Utopia has so many faces, more or less adequately theorized. First we will need to lose the old order, abolish its downward pull… The long list of works that Fernandes quotes in her film testify in favour of her bold hypothesis, with pictorial strategies that defy the rules of gravity – including such canonical works as Malevich’s Suprematist paintings of bouncy geometries that could be new urbanities as seen from space, or a discharge from God’s own confetti gun. Hilma af Klint’s signature work Group IV The Ten Largest no. 3 Youth (1907) defies categorization, poised as it is between high abstraction and something figurative: with its cartoon-like spirals and curlicues, and what appears to be flowers attached to a target for shooting practice, it looks like a spiritualist’s shot at visualizing energies invested in the making of a new cosmos. Which is probably what this mind-blowing painting is.

One of the key stakes in Fernandes’s genealogy of modernist abstraction – or so I would say – is the relation between play and leisure. They are proximate to one another, even contiguous from a certain perspective, and yet so different. What (the adult world calls) play is a universal referent that is never far removed from utopia. Play isn’t tainted by a dialectics of Enlightenment: it never promised progress to eventually flip into barbarism. According to Friedrich Schiller’s post-Enlightenment theory, play is a sensuous and edifying, macro-pedagogical social process: if we all heed the call of our Spieltrieb, or ‘play drive’, civilization can keep its violent impulses in check and fully realise itself as human. In the twentieth century, play was consistently valorised across the various artistic avant-garde movements, as a wide ranging common denominator connecting – among other things – Dadaist anarchy, the Modernist genius’s blessed serendipity (Picasso: “I seek not, I find”) and anti-authoritarian playfulness, as expressed in the Situationist International’s slogan from May ‘68: ‘under the paving stones, the beach!’ (where you can play in the sand, presumably). In short, play promises a self-destructive Western civilization that it can get back on its feet and that it has a future. Regarding the West’s no less impressive capacity for annihilation of its others, the question is if play can rescue them, too; but that is another discussion, one that relates to that of the child as a regulatory figure between civilized and uncivilized.

Leisure, on the other hand – and as Fernandes also observes in the quote above – is already inscribed in the political economy of productivity. Very simply put, the hamster wheel and the Ferris wheel are the two extremes between which the working classes are shuttling during their working week (the so-called leisure class is above all that, no doubt, preferring other temporal organisations of their lives, and other types of wheels). Leisure doesn’t promise the future, the way that play does, but is irremediably part of the present, its symbolic orders and commodity exchanges. It is born from a no less productive rationale than labour, in terms of regeneration and ‘refuelling’ of the work force. It is so hard to get it right – and not just because the weekend is all too short: the problem is that theme park is notoriously spurious, as per Céline’s hysterically upbeat visit to a Parisian theme park in the opening quote, in which entertainment equals pretense. Also to social philosopher Lewis Mumford, Coney Island was a “means of giving jaded and throttled people the sensations of living without the direct experience of life—a sort of spiritual masturbation.” You could be forgiven for seeing the theme park, as an outgrowth of Western industrialised urbanity, as some sort of Taylorism in extremis, what with those precisely coordinated assemblages of bodies, machines, and cash that produce kicks and thrills and bellyaches. I guess you can even compare the Philistine standard response to non-figurative art, ‘You call this art?’ with the scepticism that accompanies the theme park’s visceral simulations: is this actually an experience? Is it really freedom?

So leisure, it would seem, trails in the slipstream of play, more grown-up and no less conceptually multifaceted. However it belongs to the contemporary side of the story that play isn’t what it used to be. Arguably it is currently on the brink of exhaustion. This is a cultural condition that Fernandes has explored in her video For a Better World (2012) that documents a theme park for children in Lisbon where children can play at being grown-ups. It is a meltdown between the subjectivities of child and adult, capitalism and carnival, work and play: at Kidzania children work as a check-out assistant, firefighter, doctor or burger-flipper, to earn Kidzania-money to maintain the lifestyle they momentarily adopt in the playland, among copies of existing shopping and fast food chains, scaled down to kid-size. In Fernandes’s registering we see children jump down the rabbit hole of play to emerge in a corporate version of the adult world, where they over the course of a few hours play compacted sequences of work, shopping and leisure activities, all in the context of a capitalist utopia circumscribed by real-world branding. If leisure is somehow scripted by society – structured by work and punctuated with happy endings – then Kidzania is leisure eating its way into play.

Another leg or vector in Fernandes’s conflation of modern social and art histories is the relation between abstract art and leisure culture. A poignant historical example is the aesthetic showdown that took place across the Zonenrandgrenze, the border between the former East and West German states, in the 1950s. From the Western side, a premise of this debate was that abstraction represented a ‘world language’ (a Weltkunst), capable of transcending ideological frontiers as an – essentially modern, essentially free – form of universal human expression. This in contrast to figuration and realism, which by association with Socialist Realism, the official art of East Germany, were suspected of totalitarian tendencies. Promoted by the West German mass media and its cultural and economic elites, abstract art here became an aesthetic measure of post-war success and prosperity. To this extent, it could be seen as a cultural boom in parallel to the various aspects of the consumer boom unleashed by West Germany’s Wirtschaftswunder or ‘economic miracle’ in the areas of food, fashion, interior design, and holiday travel. At this point in West Germany, abstract art was one of the consumer goods that could mark a boundary between mainstream forms of leisure culture and ‘the more “expensive” places’ that Céline mentions in the quote at the beginning of this text, including art galleries and museums. By the late 1950s, abstract art had achieved a virtual monopoly of the West German national art markets and public opinion, helping to pull up the Bundesrepublik from the miasma of post-war poverty and collective guilt towards the totally bearable lightness of Americanization.

The socialist realists, on the other hand, kept both feet on the ground, and aligned creativity with labour – the losers. To American Cold War ideologue Arthur Schlesinger, totalitarian man was someone ‘tight-lipped, cold-eyed, unfeeling … as if badly carved from wood, without humour, without tenderness, without spontaneity, without nerves’. Apparently there was no sense, or concept, of neither leisure nor play on the dark side of the iron curtain: imagine how Schlesinger would have imagined a rollercoaster full of totalitarian men and totalitarian women, going up and down, all stony-faced and mum. If it seems improper to drag the canon of modernist abstraction through a theme park, it is sobering to consider how mid-twentieth century bloc politics placed it firmly on the side of amusement, with all the commodity relations this implies. What is more, it is tempting to extend Fernandes’s characterisation of abstract art into a critique of the logocentric assumptions that underpin the West as the site of progress – for instance in distinction to all those notionally backward cultures that don’t organise their world according to the (Christian, Platonic, Cartesian…) verticality of metaphysics. Cultures where people still sit on the ground. The event hovers, mused Deleuze in The Logic of Sense (1969). Deleuze exemplifies the event – the Event in its essence, not an actualized event among others – with the battle:

But it is above all because the battle hovers over its own field, being neutral in

relation to all of its temporal actualizations, neutral and impassive in relation to

the victor and the vanquished, the coward and the brave; because of this, it is all the more terrible.

The Event ”hovers” because it is incomparable and indifferent to attempts at naming it, impermeable to both names and prayers. Like a UFO it arrives in the empty sky, eluding its own actualisation by its refusal to touch ground and take part in human time and language. However Deleuze’s elegant figure of thought is impossibly out of reach of the art work as historical and material fact: an art that hovers in untouched virtuality sounds like a perfect, self-indulgent fantasy of artistic autonomy. Also in this perspective, maybe it wouldn’t hurt the modern Western tradition of abstraction to come down to earth a bit.

Finding pleasure in leisure calls for true, unbounded creativity, one that thinks and plays with the body. One of the works quoted by Fernandes in Never Touch the Ground is Hélio Oiticica’s piece of vitalist concretism Metaesquema no. 348 (1958). Later, Oiticica would propose the neologism ‘creleisure’, a pun on leisure and crear (to create), and crer (to believe), that denotes a kind of production of desire inherent to creativity that transgresses a normal valorization between states of productivity and non-productivity. In this strange way, laziness becomes a paradigm for aesthetic production and reception: “Not to occupy a specific place, in space and in time, as well as to live pleasure or not to know the time of laziness is and can be the activity to which a ‘creator’ may dedicate himself,” Oiticica writes in the rambling essay “CRELEISURE” (1969). Later he would create works that aptly support Fernandes’s hypothesis of a physically suspended art, in his installation series Cosmococas (1973), a ‘quasi-cinema’ that with slide shows of cocaine drawings offer pockets of time and space where reality principles are put in abeyance, suspending viewers’ bodies in hammocks or a swimming pool, disconnected from the passing of time: Sabeth Buchmann nicely calls Oiticica’s take on it a ‘deviant re-sublimation’, a concept of leisure that overshoots (or deliberately shoots down) its economical functionality and instead sets it to work in queer and socially dissonant registers.

All of which adds to Fernandes’s ambiguous dialogue with – or critique of – modern art, and how we can begin to reconstruct our relation to it. After a trip in several gruelling rides, modernism’s masterpieces and linear narratives are well and truly debunked and tangled up, their canonical pathos melting in their sunny day out from the pantheon, ice creams and candyfloss in hand. Obviously, in Fernandes’s work Western modernist abstraction is also re-affirmed as the principal of the art we call contemporary, the ur-root of which her own project is a frivolous outlier. Because there are no easy ways out for anyone involved, Dr. Fernandes proscribes shock treatment to modern art history and the social contexts from which it cannot be separated, as if she found them in a state of suspended animation. In her work there is a sense of trying to re-connect to play against capitalist abstraction, Marx’s famous term for the way in which the workings of capital will make social life alien and let everything solid melt into air. We know, though, that children through play inscribe their subjectivity on all the “actual milieus” (Deleuze) through which they move: there is reason to hope that at least the children will always find a place to play – including in apparently hopeless, over-determined places like Kidzania. There is nothing like play to send it all up in the air. But now I am possibly reverting to a utopian register? In any event, it is certain that the playful take on art history in Never Touch the Ground “de-abstracts” artistic abstraction by reclaiming the modernist tradition’s, weighty relation to the human body and its social contexts, then and now. In Marx’s famous phrase, history repeats itself, first as tragedy, second as farce. To translate this to our present concerns: first history is a hovering battle, second a shooting tent in the amusement park. In his essay “The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte” (1852) Marx foresees how the revolution will evade the fall from tragedy to farce by bringing into action the self-reflexivity of revolutionary practices: this is a process where historical subjects “criticize themselves constantly, interrupt themselves continually in their own course, come back to the apparently accomplished in order to begin it afresh (…) until a situation is created which makes all turning back impossible, and the conditions themselves cry out: Hic Rhodus, hic salta!” Prove what you can do, here and now! In this continuous self-critique – that Priscila Fernandes shows art must find its own ways to establish, beyond the Marxian schema of tragedy and farce – history is owned by no one, or by all. Surely there is no better reason to jump for joy, up in the air.

READ MORE...

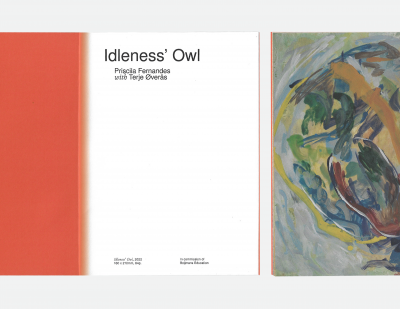

Marta Mestre

In occasion of the solo exhibition Leisuse School, CIAJG, PT

Published in 2022

By CIAJG

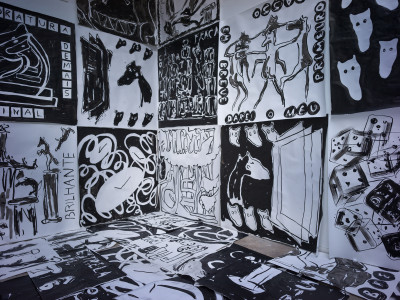

PAINTING ROOM

Zéro de conduite, by French filmmaker Jean Vigo, was the point of departure Leisure School of Priscila Fernandes, at CIAJG. The 1933 film narrates the insurrections of a group of children in a French provincial school. The heroic images of these protagonists against the cruelty of the teachers and the institutions of discipline propelled the exhibition’s imagery, particularly the moment in the narrative in which a pillow rebellion erupts

in the silent, austere dormitory offering a festive rain of feathers. A mix of

revolution and tenderness, in which joy functions in a spatial and mobilizing manner, these images are pregnant with the future.

The echo of these images in the exhibition, itself spatial and mobilizing,

testifies to the ability of gestures and images to engage our gaze, independently of the specific time-space that produced them. It also inspired a different performativity of the exhibition space, alternative to the canonical forms of relationship with the public. Seven oversized tables (similar to the beds in Zéro de conduite) were judiciously scattered, each receiving a painting visible on both sides.The display created by Priscila Fernandes for the exhibition’s first room subverted the habits and meanings imposed by the museum and proposed zigzagging detours and peripatetic walks.

It seems evident, although I never talked with Priscila about the subject,

that the bed-table-supports reference the radical museographies of architect Lina Bo Bardi, particularly her crystal easels for the São Paulo Museum of Art. In the suspended paintings that Priscila installed at CIAJG, one could see human figures breaking chains (in a sort of liberating challenge) and asking the question: are we free to do whatever we like?

Another reference that seemed implicit as I wandered about the design

of the exhibition space is the thought and practice of French pedagogue and writer Fernand Deligny, who applied experimental pedagogical approaches in his work with autistic children as he searched for a mode of being that would allow them to exist even if that meant a profound change in our own mode of being. In one word, the erring and artistic character of living.

PHOTOGRAPHY ROOM

In the second half of the 13th century, an anonymous poet from the North of France recorded the oral traditions about the existence of a land of plenty called Cockaigne (Le Fabliau de Cocagne). The myth of a land of pleasures, social harmony and Pantagruelic sexual freedom where people did not age and work did not exist because there was only pure gratification was also represented in Pieter Brueghel’s painting a few centuries later. Food was plentiful, shops offered their products for free, houses were made of barley or sweets, sex could be freely obtained, the weather was always pleasant, wine flowed endlessly and everyone stayed forever young. Narratives like Cockaigne were researched by Priscila Fernandes and incorporated into her work; they consolidated her interest in the imaginary utopian space and the quest for alternative geographies where conventional morals could be discarded.

Cockaigne inspired Priscila Fernandes to question her artistic work. What do artists do in their studios? What is the nature of their work? Is it leisure?

In Labour Series, the set of photographs that took over one of the exhibition rooms, Priscila Fernandes reflects on the social models that identify artistic activity. In this series of images, the artist herself stages idleness, leisurely posing in her studio. Roller skating, artificial tanning, meditating on top of inflatable beach buoys, and other effortless gestures without a rigid schedule and free from any obligation unfold as the artist exerts absolute control over her life. As if in a mythical Cockaigne, Priscila Fernandes represents the artist immersed in her reverie, but, paradoxically (or not) she calls the images series (Labour Series), which implies a notion of organized work. Indeed, the assembly line and the standardizing of processes created by Henry Ford are not alien to the dialectics of free time and work time. As Priscila Fernandes says:

I’ve been greatly preoccupied with these questions, as an individual and as an artist. I’ve been looking at positive ways in which to engage with our current zeitgeist, ways in which to shift the focus of a society of labour towards a society of leisure. However, this brings a paradox. Leisure today is part of an ethics of work and serves to fulfil a desire to be productive, encouraging self-discipline and self-improvement. But yet, countries in southern Europe that greatly depend on tourism and leisure are perpetually deemed as lazy countries as a justification for their low economic growth. And if laziness and idleness are at times exalted as activities necessary for the development of art, poetry, literature

and philosophical thought, they are also said to promote indolent, unproductive individuals, inert, lethargic and inactive. So how can we shift the way we think and look at leisure in a positive way?

PROJECTION ROOM

One of the main labour rights conquests was the right to paid leisure. Paid holidays as a reward for work appear in article 24 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights: “Everyone has the right to rest and leisure, including reasonable limitation of working hours and periodic holidays with pay”.

In this sense, amusement parks, fairs, casinos, beach resorts and camping parks, as well as modern museums, emerged and consolidated in the light of workers’ rights, while illustrating the contradictions of capitalism. On the one hand, the (false) idea of a better quality of human life – free time for fruition and enjoyment – and, on the other, the proliferation of spaces that ensure, from the perspective of leisure, mass consumption and the spending of the capital allocated to paid holidays, i.e., the cultural contradiction of capitalism as predicted by Marx.

The parodic and speculative reading of art history and the inventions related to pleasure, woven by Priscila Fernandes in Never Touch the Ground, are, in this sense, symptomatic of those very contradictions. While, on the one hand, it offers an unexpected key, exposing a sort of blind spot in the connections between modern art and leisure-related inventions (such as the association between the invention of roller skating in 1960s America and abstract expressionism, or even between the first inflatable swimming-pools and Yves Klein’s Anthropometries), on the other hand, it draws attention, even if indirectly, to art as an instrument at the service of the ideologies of capital. Contradiction, in the guise of irony, turns Never Touch the Ground into a disconcerting reflection.

In the last analysis, the museum, an institution that emerges from the Enlightenment and the ideals for the construction of a just and egalitarian society, provides a conceptual framework to Priscila Fernandes’ reading and is an active part of those ideologies. Museums are changing their focus, from an educational perspective to an accommodation of the leisure markets. The neoliberal turn of the last decades only reinforced the museum as a social organization, increasingly copied from corporative models and neoliberal consensuses, designed to produce desires and consumers for ideas of culture and blockbusters while operating directly on the narratives that should and should not make up a society and its forms of cultural expression, i.e., cultural logic is increasingly governed by consumption and entertainment.

In this sense, Priscila Fernandes’ work achieves a particular resonance and critical power in the context of the museum. By reflecting on the work-leisure binomial she (also) makes us think about the museum that we would like to have, asking us to imagine alternative models, ‘instituting institutions’, in philosopher Cornelius Castoriadis’ sense, that may express our ability to go on imagining and fictionalizing.

READ MORE...