In 1890 Paul Signac painted one of his most bizarre neo-impressionist paintings - Opus 217. Against the Enamel of a Background Rhythmic with Beats and Angles, Tones, and Tints, Portrait of M. Félix Fénéon in 1890. When his friend and political activist Felix Fénéon saw the painting he though it had made a hole on his wall.

For long that I've been intrigued by the peculiar aesthetics of neo-impressionism, it's scientific backbone, and how pointillism was used as a tool to inspire an anarchist revolution.

In Against the Enamel, I let the painting of Signac spiral continuously around it fulcrum in a LED video animation.

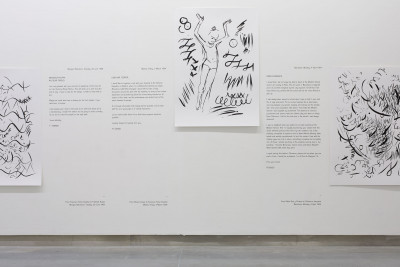

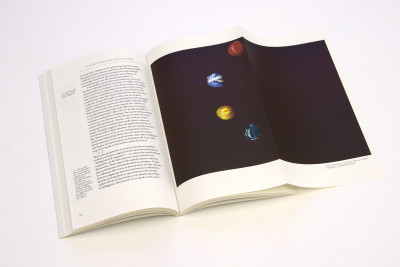

Exposed under the eradiating beams of light from the video, five cast iron sculptures lay on the ground, as if in a reverent procession towards the explosion or implosion of the moving image. The sculptures shapes (inspired by primary art school manuals from the turn of the 20th century) and their materiality (cast iron), speak of an era when the focus on education and demands of labor were closely related. An era where industrial production promoted exercises intended to create working habits: a sense of effort, patience and perseverance in the students. I see this approach towards the discipline as a moral, as well as aesthetic issue: the discipline of the hand that draws, is connected to the discipline of the body and moral conduct in general.

In the first exhibition of Against the Enamel, at TBG+S in Dublin, the installation included a site-specific intervention. Before being a gallery, TBG+S was once a clothing factory (opened in 1932 by T.J. Cullen Limited). The original factory pillars of this gallery were exposed alongside the supporting pillars of the 1990's extension to the gallery, a symbolic gesture that teared back the layers of the buildings past and present use.